So* I’ve been reading a post by a fellow blogger about how taking an academic course generates empathy in us for our students, and I’m thinking, “Yeah, tried that once.”

Last year, I created a reading blog to follow my students in their extended reading program. I read a novel in French as they read theirs in English. Did I experience empathy? Well I found out what it is like to read really really slowly. By obsessively examining my reading practice, I discovered that I was marginally less proficient in reading French than I thought. But did I really develop empathy for my students? No, I was having a good time. Reading and self-obsession are my two favourite hobbies (well besides #catsofinstagram) (And let’s just say that there’s a fine line between reflective practice and narcissism; in fact they are part of the same Greek myth.)

To really mimic their experience, I would have to be kidnapped, transported to a place halfway across the world where the time was always 12 hours wrong. I would then be forced to read books I didn’t want to read and have to pretend I liked them. To receive credit, I would be compelled to join an organization that was illegal in my own country and participate in an activity as potentially addictive as online gambling or crystal meth.** So no.

So what is empathy really? Empathy is when students cry and you cry with them, and it sucks because it’s really tough to teach separable phrasal verbs with mascara running down your face. It scares the students and makes them feel bad for disturbing you.

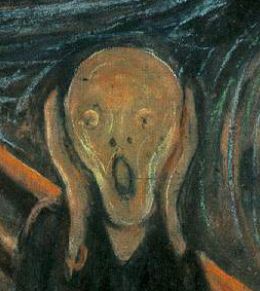

True empathy is a dark primal emotion***, as volatile as lighter fuel. It’s not necessarily something you want to have around when you’re teaching. In fact, perhaps we are more effective without empathy.

I think Malcolm Gladwell makes a similar point about surgeons, but I don’t acknowledge his existence any more after that obnoxious article he wrote about being a jackass at his best friend’s wedding.

Before I started working in settlement, I had a kind of awe of anyone who had led a life of suffering. I felt that they were somehow ennobled and not to be judged by conventional moral standards.

That all changes when you get a class full of people who — well let’s put it this way: very few people leave their jobs and uproot their families and get on a plane because they are so happy with their life that they want to spread the joy.

They all come from some kind of suffering, but suddenly they are not so noble. You don’t judge them exactly and there are all sorts of things that you take into consideration, but even so, a teacher soon realizes that some students are better at getting along with each other and contributing to the community than others****.

If you encourage the behaviours of those students, you’re going to have a safer and more collaborative space for everybody, and they might even learn more. So you can either melt into a puddle of sorry or impose some norms on the classroom.

And so yes, one does have to turn off one’s humanity to a certain extent. It’s surprising how quickly this surgeon mindset takes hold.

I remember the first time a student cried in front of me, the first time a student told me of a friend being killed, the student who told me of her children being taken away by social services.

There were times when I lost it*****, but more often than not, I would hear my own voice saying, “So tell me what happened; tell me what I can do.” Often I was shocked by my words. How could I not be destroyed by this terrible story I was hearing? It was as if some mechanism had malfunctioned in my brain. But had anything been lost? Would I have been a better person had I stayed connected?

Let me give you an example. Back in the days before cellphones, daycares used to call the main school phone if there was a problem with the child. The secretary would then page the parent on an all-call throughout the school. Then the parent would have to go to the office to take the phone call. Once when a woman was paged, she asked me to walk with her. As we made our way down the stairs and along the hallway, I could see that she was terrified. I walked calmly beside her, keeping my steps even so as to encourage her body to slow its pace. Would I have been a better person if I had empathised, if I had imagined feeling that terror for the safety of one of my children? Perhaps, but I would never have made it down the stairs, and then what good would I have been?

There are times when the best thing we can be is a mirror that reflects back a person’s emotions, but sometimes that is not what is needed. If we both feel our knees buckle, how can we keep from falling?

*Yeah, yeah, yeah, I read that banned words article. Not going to change, though.

**I know — I am also participating in this addictive activity, but it’s different when it’s voluntary. It’s the difference between becoming a heroin addict through one’s own actions and that episode of Starsky and Hutch.

*** Read this if you don’t believe me. Read this too: it’s not as relevant, but it’s really good.

****George Monbiot articulates this phenomenon nicely here: “I have seen people undergo astonishing trauma and emerge scarcely changed by the experience. I’ve seen others thrown off balance by what look like insignificant disruptions: the butterfly’s wing that causes a brainstorm. We cannot expect a system as complex as the human mind to respond in predictable or linear ways.”

*****like here.

January 16, 2016 at 1:29 am

I recently had a male student tear up (a few ran down his face actually) in my office because he felt bad about himself for producing work that didn’t score well, despite spending time and effort trying. I felt his frustration and disappointment. I wanted to reach out and touch his leg or hug him, but I knew that I couldn’t. Because of the nature of the stakes in our program, I’m usually more detached, but in this case, I understood his feelings and felt my heart melt a little.

LikeLike

January 16, 2016 at 2:01 am

Thanks for sharing that — it’s interesting how some things really touch a nerve and others leave us detached.

LikeLike